Artie is a fully managed real-time streaming platform that continuously replicates database changes into warehouses and lakes. We automate the entire data ingestion lifecycle, from capturing changes to merges, schema evolution, backfills, and observability, and scales to billions of change events per day.

TL;DR

On AWS RDS, your WAL can keep advancing even when your logical replication stream is completely idle.

RDS writes internal heartbeat records that generate WAL — but those writes never appear in the logical stream. From the CDC consumer’s perspective, nothing is happening. From Postgres’s perspective, WAL keeps moving forward.

If you’re using replication slots, that mismatch can cause WAL files to accumulate indefinitely during long idle periods.

We fixed this by advancing the replication slot using protocol-level keepalive messages — but only under strict safety guardrails — so WAL can be recycled without risking data loss.

Why an Idle RDS Database Still Generates WAL

You’d think an idle database wouldn’t generate WAL. No inserts. No updates. No deletes. No DDLs.

So where is the WAL coming from? On AWS RDS, the answer is: RDS itself. RDS runs an internal background process that writes periodic “heartbeat” records to a system table called rdsadmin. These writes happen roughly every five minutes. They’re part of RDS’s internal health checks and monitoring. Those writes generate WAL. But here’s the important part: they are not included in your logical replication publication.

So from the perspective of logical decoding:

- No new change events are emitted.

- No transactions appear.

- The replication stream looks completely idle.

But from Postgres’s perspective:

- The WAL head keeps advancing.

- New WAL segments are created.

- The database is not actually idle.

This creates a subtle mismatch. Logical replication only sees changes to tables included in the publication. Internal system writes don’t qualify. So your CDC consumer sees silence — while WAL continues to move forward underneath it. If you’re using replication slots, that difference matters.

Replication slots tell Postgres:

“Do not delete WAL older than the last LSN I’ve confirmed.”

If your logical stream is idle, the slot doesn’t advance. If the WAL head keeps moving because of RDS heartbeats, the gap between those two LSNs grows. And Postgres will happily retain every WAL segment required to preserve that gap. When this happens, your “idle” database can start consuming disk at a steady, invisible rate.

A Quick Mental Model of Postgres Logical Replication

You only need five concepts to understand this failure mode:

- Write-Ahead Log (WAL): Every change in Postgres is written to the Write-Ahead Log before it touches the data files. If something writes to the database, it generates WAL.

- Log Sequence Number (LSN): An LSN is just a position in that WAL stream. The current WAL head keeps moving forward as new records are written.

- Publication: Logical replication only emits changes for tables included in the publication. If a write happens outside that publication, it still generates WAL — but it won’t appear in the logical stream.

- Replication Slots: A replication slot tells Postgres: “Don’t delete WAL older than the last LSN I’ve processed.” If the slot doesn’t move forward, WAL can’t be recycled.

- AWS RDS Heartbeats: To ensure your managed database instance is alive and healthy, AWS RDS runs a background process that writes a "heartbeat" to an internal table called

rdsadminevery 5 minutes.

The Real-World Scenario

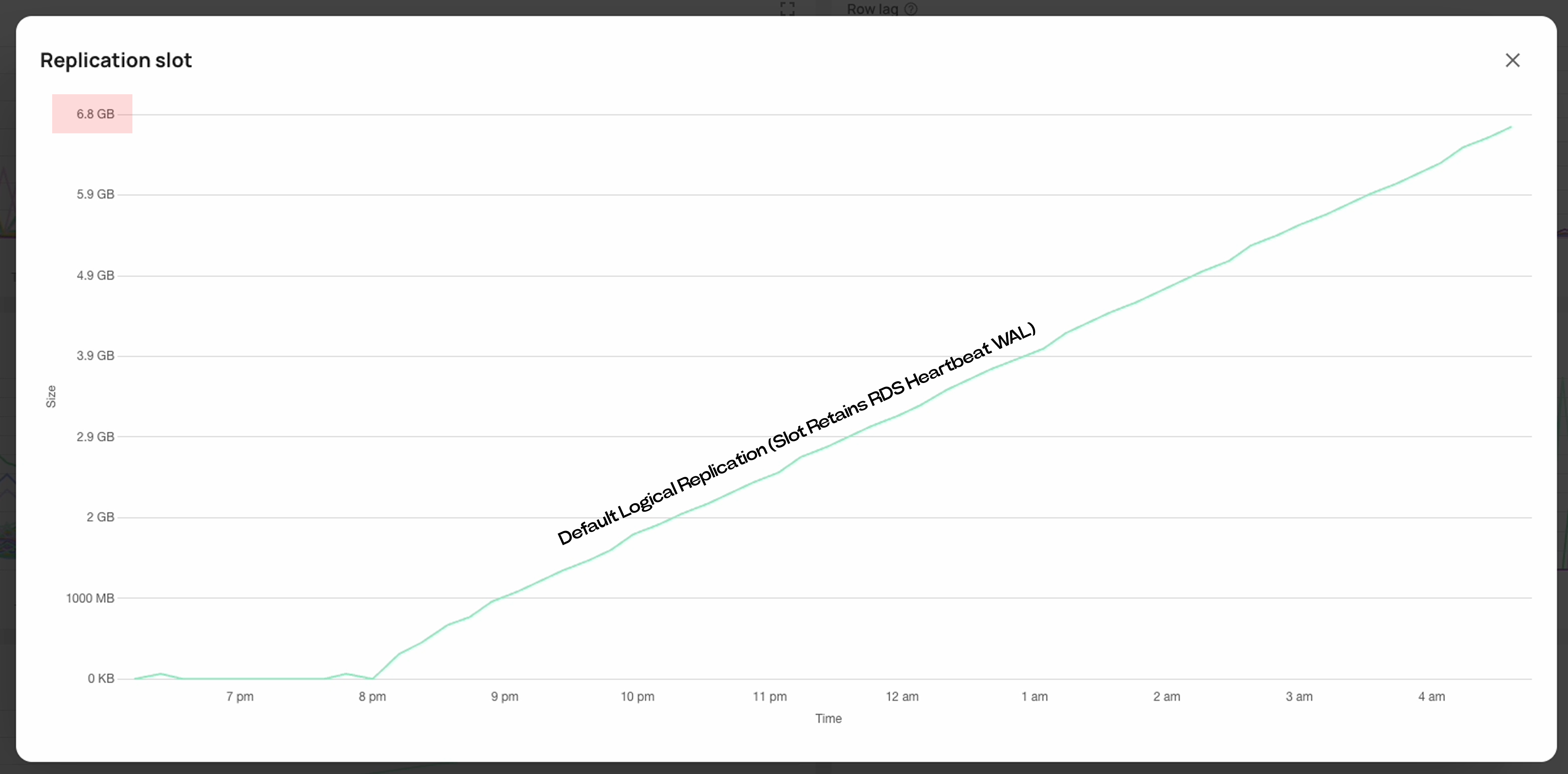

We first noticed this in one of our staging environments. The production database was busy and behaved exactly as expected under logical replication.

Staging was different. Staging followed a pattern: bursts of heavy writes during integration tests, followed by long periods of inactivity.

From the connector’s perspective, everything was caught up. But disk usage kept climbing. During those idle windows, AWS RDS continued writing internal heartbeats to the rdsadmin table roughly every five minutes. Those writes generated WAL. But they did not appear in the logical replication stream.

Over time, that steady accumulation created real disk pressure. Left unattended, an “idle” database could consume tens of gigabytes of WAL over the course of a week — without a single application write. Eventually, replication slots would become unhealthy or invalidated. Recovery required manual intervention and, in some cases, full backfills.

Nothing was broken. Postgres was behaving correctly. RDS was behaving correctly. Logical replication was behaving correctly.

But together, they created a failure mode that only appears under prolonged inactivity.

The "Idle" Database Paradox

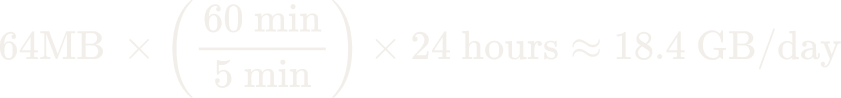

RDS heartbeats generate WAL roughly every five minutes. With a default 64MB WAL segment size, that can translate to roughly 18GB of retained WAL per day — even if no application tables are changing.

That’s what makes this failure mode dangerous. It doesn’t show up under load. It shows up when nothing is happening.

What Happens When WAL Gets Too Big

To put this in perspective, consider a typical staging database provisioned with 100 GB of storage. At an accumulation rate of ~18.4 GB/day, an otherwise idle database can exhaust its available space in under a week. Because this growth is invisible to logical replication metrics, it often goes unnoticed until disk pressure becomes the first signal.

The consequences of this accumulation are severe:

- Database Panic: When disk space is exhausted, Postgres will panic and shut down to preserve data integrity, resulting in immediate downtime.

- Replication Slot Invalidation: If max_slot_wal_keep_size is configured, Postgres may drop the replication slot to protect the database. While this preserves disk space, it breaks the CDC pipeline and requires a painful backfill to recover.

- Operational Debt: Recovery often requires resizing volumes or manual cleanup. Worse, if the slot is invalidated, a full historical backfill is required. And backfills aren’t free. They consume time, compute, and operational attention. They may also introduce downstream load or require reprocessing large volumes of data in warehouses and analytics systems.

The Solution: Using Keepalive Messages to Advance Safely

The fix wasn’t to invent a new mechanism. It was to use one that already exists.

As part of the logical replication protocol, Postgres periodically sends keepalive messages to connected consumers. These messages confirm that the connection is still active and include the server’s current WAL position (ServerWALEnd), even if no logical change events are being emitted.

That detail matters. During extended idle periods, we can observe that:

- No logical replication messages have been received.

- No transaction is in progress.

- The server’s reported WAL position continues to move forward.

In other words, we know WAL has advanced — but we also know there are no in-flight application changes waiting to be decoded.

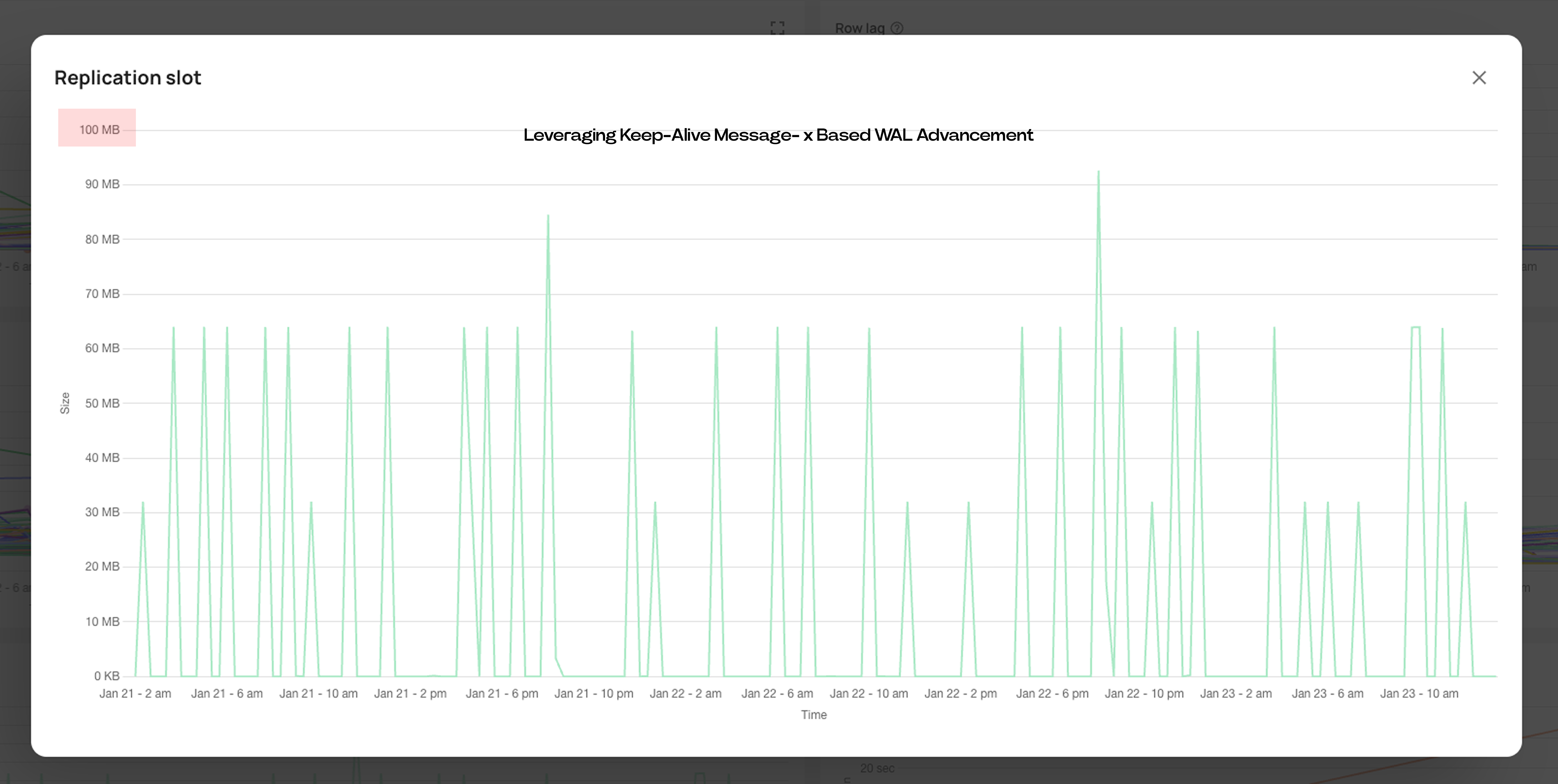

Under carefully defined conditions, we treat the keepalive’s ServerWALEnd as a safe point to advance the replication slot. This allows the slot to move forward even when the logical stream is quiet, which in turn allows Postgres to recycle old WAL segments.

We are not skipping transactions. We are not bypassing logical decoding. We are advancing the slot only when we can prove that no published changes exist between the current position and the keepalive LSN.

That distinction is critical. The system remains fully correct under load. During active write periods, replication state advances exclusively through logical decoding output, exactly as intended. The keepalive-based advancement only activates after prolonged inactivity, when the absence of decoded changes becomes meaningful.

With that guardrail in place, idle CDC pipelines no longer accumulate unbounded WAL simply because RDS is writing internal heartbeats.

Engineering the Solution in Go

Moving the replication slot is easy. Moving it safely is not.

If you advance a slot past the start of an uncommitted transaction and that transaction later commits, you’ve permanently skipped data. There’s no retrying that.

So the design is intentionally conservative. We don’t try to detect idleness perfectly. Postgres doesn’t expose a clean signal that says, “No future commits exist behind this LSN.” Instead, we define strict conditions under which advancement is allowed — and refuse in all other cases.

We only advance when:

- We are not in the middle of decoding a transaction.

- We’ve successfully processed logical messages before.

- We’ve seen no logical activity for six hours.

- The server’s reported WAL position (

ServerWALEnd) is ahead of our current LSN.

Here's the core logic:

func shouldAdvancePositionFromPrimaryKeepaliveMessage(

pkm pglogrepl.PrimaryKeepaliveMessage,

lastXLogDataTime *time.Time,

receivedXLogDataSinceLastCommit bool,

currentLSN pglogrepl.LSN,

) bool {

// 1. Safety Check: Uncommitted Data

// Do not advance if we are in the middle of processing a transaction.

// This ensures we never split an atomic commit.

if receivedXLogDataSinceLastCommit {

return false

}

// 2. Safety Check: Liveness

// Ensure we have successfully received at least one XLogData message previously.

if lastXLogDataTime == nil {

return false

}

// 3. The 6-Hour Rule (Heuristic)

// We only auto-advance if we haven't seen relevant data for 6 hours.

// This acts as a safety valve to prevent skipping data during extremely

// long-running transactions or batch operations.

if time.Since(*lastXLogDataTime) < 6*time.Hour {

return false

}

// 4. Advance only if the server is actually ahead of us.

return pkm.ServerWALEnd > currentLSN

}The Result

With this logic in place, idle CDC pipelines no longer accumulated unbounded WAL during periods of inactivity, neutralizing the "ghost data" problem for our customers.

- During active periods: Replication state advances exclusively through application-level logical decoding output. Transaction boundaries and ordering semantics are unchanged.

- During idle periods: After six hours with no table-level changes, the replication slot may advance based on keepalive messages alone, allowing it to move past accumulated

rdsadminnoise without skipping committed data. - Outcome: WAL files are rotated and deleted correctly, storage usage remains flat, and staging pipelines run indefinitely without manual intervention.

Conclusion

This failure mode doesn’t show up under load. It shows up under silence.

On AWS RDS, WAL can continue advancing even when your application tables are idle. If you’re using replication slots for CDC, that gap can quietly grow until storage becomes the issue.

Handling idle periods explicitly isn’t an optimization. It’s necessary for long-lived CDC pipelines in managed environments.

If you’re running logical replication on RDS, it’s worth testing how your system behaves during extended idle periods. Silence can be just as dangerous as load.

We build and operate real-time data infrastructure like this in production. Join us, details are on our careers page!